Rice cultivation originated in China over

4,000 years and spread all over Asia. Rice today is not only a major cereal

crop in the region but also a way of life.

It contributes about 40 to 70

percent of the population's total calorie intake. Therefore, sustained

production and increased productivity of rice is critical for food and

nutritional security in Asia.

Now a

“peer reviewed“ study says production of rice:

"the world's most important crop for ensuring food security and

addressing poverty—will be thwarted as temperatures increase in

rice-growing areas with continued 'climate change'.

The net impact of projected temperature

increases will be to slow the growth of rice production in Asia. Rising

temperatures during the past 25 years have already cut the yield growth rate by

10-20 percent in several locations. Applying typical global warmist tactics,

they refuse to shed light whether there are other locations in the world where

the reverse trend applies!

Published in the online early edition the week of Aug. 9, 2010 in Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences — a peer-reviewed, scientific journal from

the United States — the report analyzed six years of data from 227 irrigated

rice farms in six major rice-growing countries in Asia, which produces more

than 90 percent of the world's rice.

World demand for rice by the year 2025 is

projected to be about 765 million tonnes as compared with the present

production of around 556 million tonnes. This leaves an estimated supply-gap of

109 million tonnes to be filled in 15 years. It is argued that due to low land

availability and high rate of land degradation in Asia, crop land expansion is

no more an option to fix such a gap. According to the International Rice Research Institute(IRRI):

“….the possibility of increasing the rice area is almost exhausted in

most Asian countries. With little expansion in area and slowing yield

increases, growth in rice production has fallen below growth in demand as

population has continued to increase."

What is lost sight is that there are several

agronomic methods for upgrading marginal land into productive arable land. For

example, countries like India have practically demonstrated that it is possible

and cost-effective to restore productivity to marginal soils through

micro-watershed development techniques.

Nevertheless, it is further argued that if the continent has to meet this huge

demand-supply gap, it must do so mostly by taking quantum leaps in productivity

in rice cultivation. Now this “peer reviewed” study claims that this strategic

route too is also limited due to ‘Climate Change'.

"We found that as the daily minimum

temperature increases, or as nights get hotter, rice yields drop,"

Jarrod Welch, lead author of the report and

graduate student of economics at the University of California, San Diego.

The catastrophic message implicitly projects Asia to face stark hunger by 2025,

a practical throwback to the time when environmentalist Paul Ehrlich scared the

world by saying the world faced prospects of mass starvation by 1970!

The full report could be downloaded here and the supplementary

information here.

Why temperatures

thwarting rice production is complete nonsense

FAOSTATS - Global vs. Asian Rice Productivity

Even a cursory glance of the FAO graph should

make it evident that all individual country trends are up. This is so, even in

the case of lowly Cambodia occupying the bottom rung. Simply put, in all Asian

countries the predominant trend is that rice yields are all increasing in an

environment where in both temperature and CO2 have been rising in the period

the graph depicts. Such a perfect correlation is An Inconvenient Truth, as they

really need to ask why rice productivity is rising at all when it is supposed

to decline according to the AGW theory. Proved wrong, they now have the cheek

to ask why it is not rising fast enough.

The incline of the slopes in the graph does confirm however that the percentage

of annual increase is tending to slow down or plateauing which is however

very different to saying productivity is turning negative.

“..Cut the yield growth rate

by 10-20 percent in several locations”

is a clear acknowledgment of this fact by

this study. Simply put, yields are still rising, just not fast enough, though

more and more rice is produced every year. Despite the entire hullabaloo

created by the media on the top-line finding of this study, the conclusion of

the study is not new - it is well known in many countries yields are

plateauing. Now there could be many reasons why this could be happening.

According to the IRRI:

“An important factor accounting for the slowdown in yield growth is the

reduced public investment in agricultural research and development (R&D).”

In fact, agriculture lends itself to

multivariate statistical analysis, as yields are a result of several factors

interacting together. Yet the study adopts a uni-variate analysis approach by

treating all other variables as a constant. This is an excellent method by

which you can establish yield correlation with practically anything under the

sun, even the number of times the farmer goes to the temple in a day!

Correlation as we all know does not establish causation. However, this is what

this study exactly does with this approach.

Now a desired or targeted maximum yield is a very different ball game from potential

maximum yield of a particular genetic species combined with a particular set of

management practices. The study mixes up between these two concepts.

In context to potential maximum yield, plateauing is not anything surprising.

Eventually, we will reach the upper circuit, as there would be limits to the

amount we can tweak or modify as what we are primarily dealing with are finite

biological systems. A good analogy is the speed of human beings. The

world record for 100mts stands at 9.6 secs. Whatever techniques adopted it

would be perhaps inconceivable that this record can go below 8 secs, as there

are limits to human beings prowess. This is why athletes are tempted to taking

performance-enhancing drugs.

Similarly further increases from traditional genetics are becoming more

difficult as there are intrinsic limits to the biological system or set of

management practice. Unless plant genetics are changed or a super

fertilizer or plant growth hormone, natural or chemical, discovered, it will be

very difficult to bring about quantum leaps in productivity. As they say, it is

foolish to expect different results while doing the same thing. We need to

change something to get a different result. This is nothing but common sense.

So the central narrative of the study simply states the obvious.

Notwithstanding this, what made the conclusion of this study particularly

controversial is its link with climate change. It admits yields are increasing,

but productivity growth is slowing down and speciously linked this to global

warming viz. high temperatures to be blamed.

Vietnam and Cambodia illustrates how silly this proposition is. Vietnam has the

fastest growth in rice yields, just behind China while Cambodia occupies the

bottom rung. Agro-climatically, both are very similar being neighbouring

countries, in fact lying within the same latitudes. This clearly illustrates

that the climatic factors are not the main drivers of yields but other factors

like technology, management practices or political situation such as war are

more significant. Take Cambodia for instance - The period 1972-81 was where the

Pol Pot’s agrarian reform and killing fields, wrecked agriculture in the

country almost irreversible. However, look at Cambodia’s productivity curve

again. It has once again picked up momentum again.

We can even ask if high temperatures per se

are detriment to agriculture, what explains the significant shrinking of Sahara

desert. This is what National Geography commented:

“Villagers herd goats near windblown sand dunes in the Sahel region of

Niger, North Africa. Vast swaths of North Africa are getting noticeably lusher

due to warming temperatures, new satellite images show, suggesting a possible

boon for people living in the driest part of the continent.”

In fact, warming is beneficial to agriculture

is accepted in the extract of the study itself:

"...Higher minimum temperature reduced yield,

whereas higher maximum temperature raised it."

It has to be, as any agriculture textbook

will tell us that the optimum climatic conditions for rice are hot and humid

climate; best suited for the regions having high humidity, prolonged sunshine.

The study however takes to stating the obvious again:

“Up to a point, higher day-time temperatures can increase rice yield,

but future yield losses caused by higher night-time temperatures will likely

outweigh any such gains because temperatures are rising faster at night. And if

day-time temperatures get too high, they too start to restrict rice yields,

causing an additional loss in production.”

Of course, high temperatures (Tmax) do thwart

rice production except that the triggering point has not been reached yet.

Otherwise they would be growing rice in Siberia by now!l. The study itself

states:

“Most of the sites are in areas where monthly average Tmax is

considered to be high (>33°C) during the reproductive or ripening phase of

one of the annual crops.”

However, the range of rice's temperature

tolerance is between 20-40°C during its growing season showing there is much more buffer to

go before any tipping point is reached to justify such alarmism. As far as Tmin

is concerned, present understanding of its impact is too rudimentary and the

study itself admits the impact of temperature is the combined impact of Tmax

and Tmin collectively, which the study methods did not reflect.

Rice productivity in most Asian countries actually

parallels the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) natural cycle. During its

positive phase, called El Niño it creates droughts. Philippines and Indonesia

are hardest hit by El Niño caused droughts. The 1998 El Niño drought caused

major declines in Indonesia and the Philippines. In the Philippines, drought

affected 70% of the country in 1998 and caused extensive damage to agriculture.

Read here.

The following sets of slides (above) are

taken from UNFCC website.

Notice no mention of temperature rise as a farming constraint- this from

UNFCC. Filipinos attribute major constraints to rice productivity to water

availability and weather extremes caused by El Niño! In India, ask any farmer

the primary determinant of rice productivity. He will point upwards and say

rains!

It is important to appreciate that ENSO is

related to another natural phenomenon called Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO).

Whenever the PDO is positive, the world warms for 20-30 years as it happened

from 1977-1998 and cools as it happened from 1945-77. El Niños tend to increase

in frequency during the positive phase of a PDO and vice versa. The PDO has

turned negative again from 2005 and accordingly we are likely to see La Niña

increase in both frequency and intensity. This means more precipitation in rice

growing countries in Asia that should boost rice productivity rates for the

next 20-30 years

Coming back to the global rice productivity

graph again, we find both India and Vietnam have steady increases from

1985-2000 in both yield and production, contradicting the minimum temperature

causes decline theory. The only negative trend is seen in the combined

Philippines, Indonesia and China data of 1998 where the decline are all

accounted for by the El Nino drought.

Given this steady productivity increase, how

do the researchers conjure up a negative trend? They carefully cherry picked

six years, not only ending with the El Niño year of 1998 but also coinciding

with a period where the globe was especially warming. Why pick 1992-1998 in

2010 is the logical question? The study as their pdf document shows; was

submitted for 'peer review' only on January 2010 and accepted by July 2010.

Smell a rat somewhere? Read on. The rat gets bigger. Willis Eschenbach explains:

“The longest farm yield datasets used are only six years long

(1994-99). Almost a fifth of the datasets are three years or less, and the

Chinese data (6% of the total data) only cover two years (1998-1999). Now, if

they were comparing the datasets to temperature records for the area where the

farms are located, we could get useful information from even a two-year

dataset. But they are not doing that. Instead, they say: Data series from the

weather stations at the sites were too short to determine trends. Instead,

trends in Tmin and Tmax were based on a global analysis of ground-station data

for 1979–2004 …

Unfortunately, they have neglected to

say which global analysis of ground-station data they are using. However,

whichever dataset they used, they are comparing a two-year series of yields

against a twenty-six year trend. I’m sorry, but I don’t care what the results

of that comparison might be. There is no way to compare a two-year dataset with

anything but the temperature records from that area for those two years. This

is especially true given the known problems with the ground-station data. And

it is doubly true when one of the two years (1998) is a year with a large El

Niño.”

Statistical jugglery has been the basis of

this fraudulent claim; such practices would be a crime elsewhere!

Unfortunately, this has become the norm in the climate change industry. Instead

of being arrested and put in jail, these fraudsters are rewarded by system by

liberal grants and funds to write more reports that are more fraudulent that

justify AGW.

At the Sample Level,

Statistical Jugglery Gets Even More Interesting: The case of India

The above graph is from one of the documents

Potash & Phosphate Institute- Potash & Phosphate Institute of Canada

(PPI-PPIC), providing the rice productivity in India. From the time of

Independence, from a negative value the country has steadily increased its rice

productivity though still just half those of South Korea who has the highest

rice productivity in the world.

The sample in India is taken from just one

area in India called Aduthurai from Thanjavar District Tamil Nadu. This

district is often described as the rice bowl of the state. In terms of rice

productivity, the state also tops the country, which indicates that management

practice skills for cultivation of rice are high. Aduthurai met the following

criteria for sample selection:

"Farms at each site were selected to represent a range of the most

common soil types, cropping systems, farm-management practices, and farm sizes.

They were early adopters of Green Revolution technologies (modern high-yielding

varieties adapted to local conditions, irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides, and

mechanization) and had been under intensive management for decades.”

The Green Revolution started in India in the

70’s and together with increased productivity; it brought with it water

logging, salinization as well as to micronutrient deficiencies and organic

matter depletion. These are the farms, not only in India but also in the rest

of the sample countries that this rogue study bases its analysis. Farms already

highly deteriorated in their productive value. Therefore, it is not much a

surprise to find their productivity flagging. In fact, the real surprise is

that their productivity is found still rising!

"The

farms were not selected randomly, which is one reason we preferred

fixed-effects estimates to random-effects estimates. A consequence of the use

of fixed effects is that our results do not necessarily generalize to farms

outside the sample”

More importantly, sample selection was not

random but deliberately selected on criteria not disclosed.

“A consequence of

the use of fixed effects is that our results do not necessarily generalize to

farms outside the sample”

is further simply an euphemism that the study

findings do not reflect reality due to their non-randomness of their

sample! Moreover, only a parcel of the land and not the whole farm came

under the study. No details are provided on the sampling procedures adopted

that cast doubts on the representative character of these parcels, as in India,

parcels even with lying with a contiguous area can vary markedly.

Besides, irrigated land cannot be theoretically representative since more than

60% of Indian rice production is accounted by rainfed-farming units.

In Tamil Nadu, organic agriculture has besides made huge strides and the World

Bank estimated that as much as 20% of the state’s rice cultivation has now come

under System Rice Intensification (SRI) - primarily adopted by small and

marginal farmers. SRI is a combination of five important management techniques.

SRI encompasses transplanting of 14-day young seedlings at wider spacing with

only one seedling per hill, water management that keeps the soil moist but not

continuously flooded — alternate wetting and drying, mechanical weeding through

a rotary weeder, and higher use of organic compost as fertilizer. It works with

both hybrid and traditional seeds though some variants use chemical fertilizers

along with green manure or compost.

If Indian farmers use SRI on just 25 percent of the conventionally farmed area,

estimates are they could grow additional 5 million tons of rice—enough to feed

about four million families a year. SRI produces higher yields (40-80 per cent)

with less seed (85 per cent) and water use (32 per cent saving). The cost of

SRI produced rice however almost matches those of conventional cultivation. The

latter use flooding to snuff out weed formation. In SRI, weeds have to be

manually or mechanically removed, that involves high labour cost. Consequently,

SRI works when labour availability is high and labour costs low. However, in

states like Kerala, this system may be difficult to replicate.

Besides, Thanjavar District where Aduthurai falls is one of the locations where

the 2004 Tsunami hit. NGOs like Oxfam gave a big boost to SRI. If

irrigated/flooded rice with less than 40% of area net sown contributes nearly

70 percent of the total country’s rice production with an average yield 3.4 t

ha, SRI projects of NGOs like Oxfam, focusing on small and marginal farmers,

claimed yields much more than this average.

Therefore, it is not so much the

irrigated/flooded rice fields that India will target for quantum leaps of rice

productivity but our rainfed rice farmers. SRI has been included in the

National Food Security Mission, which aims to increase rice production by 10

million tonnes by 2012. As reported, “About 100,000 hectares is under SRI, which can be

scaled up to 500,000 hectares in the next five years.” SRI is said to

have a presence in 130 of the 500 rice-growing districts. However, that is only

1.1% of the total rice area under cultivation.

Secondly, India hopes to take a leaf out of China’s rice revolution, which was

in fact propelled primarily by hybrid rice, which was developed there in the

early 1970s. The country had extended the cultivation of hybrid rice to more

than half of its total paddy land by 1990 to emerge as the world’s largest paddy

producer.

India, by contrast, was slow in encouraging hybrid rice cultivation. The

National Food Security Mission (NFSM) has set a target of expanding the hybrid

rice cultivation to 3 million hectares by 2011-12 from around 2 million

hectares at present. Mainly targeted at irrigated rice cultivators, some of the

spin-offs of hybrids can rub off on SRI expansion.

Thirdly, within India there are significant variations in the productivity

rates of rice cultivation between growing regions in the country. The

government has announced a second green revolution, which targets the Eastern

states like West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa etc whose productivity rate lags behind

the national average.

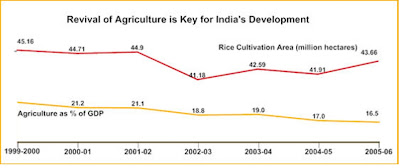

Fourthly, as could be observed from the graph

that there is a slight declining trend in net area sown for rice cultivation.

This was primarily because the price of rice was remaining very steady for an

extended period so much so that farmers began switching to alternative crops

that were more lucrative.

Due to the El Niño induced drought last year,

cultivable area dropped to less than 40 million ha. The consequence was that

total production of rice in the country was 99.18 million tonnes in 2008-09,

dropped to 89.31 million tonnes in 2009-10 against the target of 101 million tonnes.

The country lost 10 million tonnes, mainly during the kharif season, because of

severe drought conditions and this lead to price inflation, which was

additionally accentuated by the government’s decision last year to increase the

minimum support price (MSP) of rice to Rs1,000 per quintal for the common

variety, and Rs1,030 per quintal for the Grade A variety.

As a result of all

these developments, rice cultivation has become profitable again. Further, the

developing La Niño this season has brought more than average rainfall. The

result is net area sown has increased to a record of over 50 million ha this

year on the basis of which economists are predicting a huge 20% growth rate in

rice production that should see the country record a record bumper harvest of

near 110 million tons.

This alone would be an adequate to thwart

catastrophic predictions of rice productivity decline due to 'climate change'!

Here in Thailand they have 5.4 million tons of rice in storage/reserve. They only need 1.5million tons in reserve for emergencies, ie crop failures to feed the whole country. Now they are now trying to `slowly` offload the excess rice. The new harvest is coming in. Hunger. No.

ReplyDeleteIn any case, nobody has told the locals that the plolished rice, maybe 98% of all rice consumed in SE Asia, is purely energy, and that the health giving nutrients have been removed. Guess they dont need an older generation to look after.