Theoretically, strategy and crisis should

find a striking but balanced contrast; parallel in definition but opposed

in outcome. But in the case of Oxfam and Action Aid, strategy and crisis

are similar in outcome. In simple terms this means that the solutions advocated would

only accentuate the crisis, in this case, global hunger and poverty.

According to Oxfam, agriculture is the single

largest contributor to greenhouse-gas pollution on the planet, through routes

such as deforestation, rice growing and animal husbandry. Emissions include

nitrous oxide from fertilizer and methane from livestock, as well as carbon

dioxide. And with global food demand projected to double by 2050, the fear is

that agriculture's emissions will likewise double.

So Oxfam like other global warmists advocate

that to avoid such a scenario “agriculture must be more efficient”, which is simply

a euphemism to shrinking agriculture to reduce greenhouse gases, creating

more hunger and starvation based on a model of development aid piloted in East

Africa, and now to be up scaled to rest of the developing world.

Climate Smart or complaint Agriculture

inflows flows from Article 2 of the United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change (UNFCCC) which states:

“...stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a

level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate

system. Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow

ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production

is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a

sustainable manner.”

..... At the same time, agriculture is an important source of greenhouse

gas (GHG) emissions, representing 14 percent of the global total. Developing

countries are the source of 74 percent of these emissions (Smith et al. 2008).

If related land-use change, including deforestation (for which agriculture is a

key driver) and emissions beyond the farmgate are considered, the sector’s

share would be higher. However, the technical mitigation potential of

agriculture is high and 70 percent of this potential could be realized in

developing countries.”

So the so called Climate Smart Agriculture

(CSA) peddled by Oxfam and ActionAid are not something they evolved through

their own experience and learning but policies deliberately designed to align

with those of the UNFCCC. Further the main thrust of the programme of CSA is on

developing countries, not developed countries!

What is being asked of developing countries

is to transform their agriculture:

1. to enable productivity increase;

2. adapt to climate changes and

3. mitigating effect on the climate changes through

practices!

Bad enough agriculture is subject to vagaries

of the weather, Bad enough developing countries are struggling with food

security issues but now the western world wants to transform their agriculture

to an obstacle course but taking care not to impose such restrictions on their

own agriculture!

CSA policies of Oxfam and ActionAid can

either promote high and low food security and if we sieve them to categorize

these accordingly, we end up with the grid as below:

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Now as seen in the above grid - if the real

intention of Oxfam and ActionAid is really to eradicate hunger i.e. the whole emphasis

is on people, they should really choose the upper quadrant marked green. Though

most of their policies end up in the green quadrant. it is the few found at the

bottom quadrant, marked in purple whose impact can wipe out all the gains

of agriculture and worsen global hunger and poverty.

We can even understand if these policies

applied to western economies that have to bear a huge subsidy burden on their

enormous surplus agricultural production. But they are not. These policies are

mainly targeted at developing countries that have no such surpluses, many of

whom are reeling under huge deficits, experiencing mass hunger and

starvation.

As also seen from the grid both energy

and agriculture are integrated together by both Oxfam and ActionAid. For the

sake of convenience we separate the two to critique their policies.

Energy Imperialism

ActionAid

advocates: “More energy without

increasing greenhouse gas emissions” a euphemism for renewable energy - solar, wind,

tidal power.

Oxfam was even

blunter stating their renewable energy agenda:

“The vice-like-hold over governments of

companies that profit from environmental degradation—the peddlers and pushers

of oil and coal—must be broken...But the Malthusian instinct to blame resource

pressures on growing numbers of poor people misses the point, because people

living in poverty contribute little to world demand.”

Actually

Oxfam was being rather disingenuous. That was indeed the whole point. “People living in poverty contribute little

to world demand.” The planet's poorest 10

percent receives only 0.6 percent of the world's income. And sub-Saharan

Africa's population accounts for about 2 percent of global carbon dioxide

emissions.

Oxfam

admits elsewhere in their report “Certainly, the fundamentals that determine long-term food prices are

shifting, especially rising demand in emerging economies”.

So what happens to prices and supply when

developing countries start increasing their demand to ultimately seek parity to

those of the West? There would be a substantial rise in need for energy and raw

materials within rising economies, intensifying competition for that

restricted resources globally. This is the West’s greatest nightmare.

So

it follows that by keeping more and more developing country people in a

continuing state of abject poverty, ensures moderating global demand for food

or energy which in turn moderates their global prices.

Yergin

et al (1998) posed a crucial question in their analysis of fueling Asia’s

recovery:

‘Will energy spoil it?’ implying that a failure to

satisfy the enormous increases in the consumption of energy resulting from

rapid economic growth would undermine this economic miracle. So the best method

to ensure this is by raising energy costs and putting a spoke on their

development.

Barun

Mitra of the independent New Delhi think tank, Liberty Institute, in a paper observed:

“Global primary energy demand is projected to

increase on an average by 1.7% per year from 2000 to 2030, reaching an annual

level of 15.3 billion tonnes of oil equivalent from the current level of 9.1

billion tonnes. The outlook further states that the share of developing

countries in total energy demand will increase from the current level of 30–43%

while that of the developed countries will fall from 58% to 47%.”

"We are seeing a new type of imperialism

emerge, an imperialism based not on the acquisition of territory, but on a

radical environmentalist agenda, an agenda that seeks to reserve the earth and

its resources for the wealthy and elite, to freeze energy use at current

levels, and to restrict nation states from exploiting indigenous resources for

the benefit of their people.”

High-income group

countries consume 51% of the total commercial energy consumed in the world and

account for 80% of the income generated. Middle-income group countries consume

36% of the total energy while generating only 17% of the total wealth. Low

income group countries consume 13% of the total energy and generate only 3% of

the total wealth

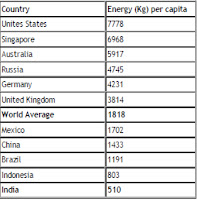

According to the World

Bank as per their 2006 data, India’s per capita energy consumption is just 28%

of the world average and just under 7% of those of the US who top the world

charts. And this is the consumption these NGOs want to freeze. The report Energy Resources: Will They Be the

Last Frontier in South Asia? concluded that “There does indeed appear to be a

nexus between the use of energy and societal development.”

Its estimated that India would take 100 years

to close the gap in incomes between itself and the high-income countries (UNDP

Human Development Report, 2005), the deficit in HDI could be removed much earlier if

energy use is tightly linked to income.

So if one limits the energy growth, they

succeed in limiting development of India itself and if they limit our

development, they limit people being pulled out of the vicious cycle of poverty

which in turn moderates global demand and prices for food or energy .

India has the fourth largest coal reserves in

the world with proven reserves above 250 billion tonnes that at current

consumption rates can be expected to last for hundreds of years. Though Oxfam

and ActionAid often talk of self-sufficiency, their advocacy aims to deprive us

the use of the resource that nature endowed us in abundance - coal - which for

that reason remains the cheapest energy source for our country. They instead

want us to depend on expensive renewable imports. The hypocrisy of the West is

best illustrated by their advocacy that developing countries should curb their

fossil fuels while they go to war to annex the oilfields of Iraq and

Libya.

Oxfam’s objective of “The

vice-like hold over governments of companies that profit from environmental

degradation—the peddlers and pushers of oil and coal—must be broken’ is merely an euphemism for policies that

encourages heavy taxation of fossil fuels, including coal even when renewable

energy capacity is just a fraction of the country’s energy mix .

Its impact on one hand means that energy

expense continue to cut a bigger and bigger hole in the family budgets of the

poor, leaving less and less for food expenditure. On the other hand, its

inflationary impact on the general economy makes food more and more expensive.

Their pincer impact increases hunger and poverty, which is ironically what

ActionAid and Oxfam claim they want to mitigate in their respective reports. To

quote the Oxfam Report on food inflation:

“In summary, these expected effects would wipe out any positive impacts

from expected increases in household incomes, trapping generations in a vicious

circle of food insecurity.”

South Asia houses nearly 1.4 billion people

which is around 25% of the world’s population; it has a sizeable energy deficit

that is filled up by imports. Although the South Asian region is a repository

of the poorest people in the world, with most number of people without adequate

access to energy than anywhere else in the world, ailed with pressing issues of

mortality and health, economically it is also one of the fastest growing

regions of the world. The vast majority of the population living in rural

areas still depend on traditional (or non-commercial) energy sources, but

gradually changing over to commercial fuels. Nearly 680 million people in rural

areas and 110 million in urban areas of South Asia are without access to

electricity (IEA, 2002). Nearly a billion people in South Asia are without

access to electricity.

My friend Barun Mitra in his paper “Sustainable

Energy for the Poor” observed

that the poor depend on traditional forms of energy that are of low intensity

and cause harm to both the environment and human health:

“Studies have revealed that women in Indian rural areas were

exposed to total suspended particulates of about 7000 micro-grams per cubic

metre in each cooking period, whereas the annual standard for outdoor air is

140 micro-grams per cubic metre. The exposure to benzo[a]pyrene was equivalent

to smoking ten packets of cigarettes per day. Their exposure to toxic tiny

particulates during a cooking cycle is 33 times greater than that of standard

ambient air pollution."

Energy and rural development are mutually dependent, and they represent one

aspect of the poverty cycle that pervades most rural areas in India. Breaking

this deadlock is one of the major challenges that developing countries face in

developing their rural areas. It is likely that problems resulting from lack of

energy will only be alleviated by investment in facilities that provide energy

on a wide scale basis.”

However the Greenpeace and The Body Shop, in

a campaign for the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in

Johannesburg, proclaimed that ‘Oil, coal and gas cannot meet the needs of the poorest, but

“positive” or renewable energy can.’ This is the same line the Oxfam and ActionAid reports

echo.

We need to pause and understand just who is

saying just what on whose behalf? A CEO of ActionAid India and Oxfam India

receives a salary of more than Rs 500,000 per month, including perks and

factoring in their terminal contract benefits. As we are all aware, a foreign

funded NGO arrival in a disaster or development setting portends rising local

prices and a culture shock. Many live in plush apartments, patronize five star

hotels, and drive SUV's, sport $3000 laptops, expensive PDA’s, mobiles and

designer wear. Their children study in elitist private schools or abroad and

they take vacations to exotic locales abroad.

How seriously should we take those living

such a lifestyle talking on behalf of those earning $1 or below per day? While

the poor does not tell these NGOs how to lead their lives and what to aspire to

in life, these NGOs in contrast feel it is their divine right to preach to the

poor. Advocating renewable energy exposes these NGO activists as having neither

proximity nor empathy with the poor and their aspirations.

We may have even respected these NGO

activists if they take $ 1 per day as a salary; power their own homes with just

one solar lantern and use cow dung as their cooking fuel. But this is not to

be. They have one standard for themselves and another for the poor. And they

call this extremely patronizing behaviour, ironically, Climate Justice!

The more radical in the Climate Justice

movement call even for banning the burning of cow dung because of its carbon

footprint! The more idiotic among them do not mind cow dung be wasted as a fuel

while at the same time advocate for agriculture to use more organic manures

(cow dung) and shun inorganic fertilizers!

So does renewable energy at least fulfill the

promise of cost effective power generation?

The Europeans have cut back on subsidies and

promotion of renewable energy, unable to afford the costs. (Read more here) The UK

government has warned its citizens that in future (because of green

energy) families, schools, offices, shops, hospitals and factories better “get used to”

consuming electricity “when it’s available,” not necessarily when they want it or need it.!

Instead of enabling India to be an UK, the

likes of Oxfam and ActionAid have dragged UK into an India - the land of power

shortages. Here kicks in the principle of fuel poverty - defined as one where a

family spends ten per cent or more of its earnings on fuel bills. The number of

estimated people living in fuel poverty in the UK is seven million which is

projected to more than double to the Green Energy policies of the UK

government.

Spain introduced the subsidies three years

ago as part of an effort to cut the country’s dependence on fossil fuels. At

the time, the government promised that the investment in renewable energy would

create manufacturing jobs and that Spain could sell its panels to nations

seeking to reduce carbon emissions.

The programme catapulted Spain to the verge

of bankruptcy. Spain finds itself saddled with at least 126 billion euros of

obligations to renewable-energy investors. The spending didn’t achieve the

government’s aim of creating green jobs, because Spanish investors imported

most of their panels from overseas when domestic manufacturers couldn’t meet

short-term demand. (Read more: here)

The Dutch who gave the world the invention of

windmills, now say they can’t afford it. When the Netherlands built its first

sea-based wind turbines in 2006, they were seen as symbols of a greener future.

But five years later, we find a different story. Faced with the need to cut its

budget deficit, the Dutch government says offshore wind power is too expensive

and that it cannot afford to subsidize the entire cost of 18 cents per kilowatt

hour -- some 4.5 billion euros last year. Read more here

When the richer Western countries can’t

afford the so called ‘green’ energy, why do the Oxfams and the

ActionAids think India and other developing countries can afford its costs by

continuing to peddle these as appropriate energy choices?

Notwithstanding this,

how did these renewable energy experiments work in India?

Tamilnadu in India for the last decade

focused capacity expansion of green field projects entirely on the so called

renewable energy that today account for more than 1/3 its power supply. In a

space of 10 years, it reduced the state from a net exporter to a net importer

of power, shaving off at least 2% of its GDP due to acute power shortages. Why?

These renewables didn’t even generate 10% of their touted installed capacity!

But in a year’s time, a much delayed coal power plant would come on stream to

put an end to the state’s power woes.

One of England's foremost climatologists,

Mike Hulme, director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, points

out that green militancy and megaphone journalism use "catastrophe and

chaos as unguided weapons with which forlornly to threaten society into

behavioral change". In his words, "we need to take a deep breath and

pause." Unfortunately,

India did not heed Hulme’s warning.

India has a gross potential of approximately

45,000 MW from wind (Ministry of Non-Conventional Energy Sources, 2004). The

present installed capacity is a little over 3,000 MW – making India the fifth

in the world. This was made possible through a set of measures meant to

encourage the use of wind power (such as subsidies and 100% depreciation

allowance), resulting in many projects coming up without proper site selection.

Most wind power sites in India are located in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra

Pradesh, Maharasthra and Gujarat where wind densities unlike in European

countries are not strong enough (200-300 W/m2 as compared to about 500 W/m2).

And what of solar power performance. India

currently produces just under nine megawatts of solar power out of which 97%

were in off-grid settings. Here is what Harish Hande, Managing Director, SELCO

Solar Light (P) Limited, India; Social Entrepreneur; Schwab Fellow of the World

Economic Forum and Magsaysay Award winner says:

...The prices have been based on large solar installations, completely

neglecting the after-sale services and sustainability of small and medium

enterprises. It is the small and medium enterprises that create sustainable

supply chains with solid after-sale services. The solar mission in its present

design is a document on how to discourage small enterprises and supply the poor

with low-quality systems.

...In 2005, subsidies in the German market had a near disastrous affect on the

systems targeted towards the poor. But never did we realize that the climate flagship

programme of India – the solar mission – would be so chilling."

So all the expensive investment in solar and

wind energy have came to naught - dead in terms of not generating power it was

suppose to generate; leaving India unable to bridge the ever widening gap

between energy supply and demand leading to power cuts all over the country. It

is this plight, the Oxfam and ActionAid reports want to accentuate by

advocating that renewable energy to be the future bedrock of India’s power

industry!

The assumption behind these so-called climate

compliant agriculture models is that global temperatures are increasing and

based on this, different regions will experience increased precipitation

and will others, reduced rainfall. The East African drought and the Sri

Lankan floods this year for example exposed how ludicrous the assumptions of

these climate smart agriculture models are. Both events were predictable and

yet NGOs were caught on the wrong foot. With the recent IPCC report

admitting the lack of linkage between climate change and extreme weather while

conceding that global warming will be taking a vacation for the next 20-30

years, the very rationale to the climate smart agriculture model has now fallen

apart.

The Oxfam and ActionAid reports besides

create an impression that Climate Smart Agriculture is a magic wand wherein all

the solutions are known but it is left to the FAO to give this warning:

“... these options involve difficult trade-offs,

with benefits for mitigation but negative consequences for food security and/or

development. For example, biofuel production provides a clean alternative to

fossil fuel but can displace or compete for land and water resources needed for

food production.

....Restoration of organic soils enables greater sequestration of carbon

in soil, but may reduce the amount of land available for food production.

....Restoration of range lands may improve

carbon sequestration but involves short-term reductions in herder incomes by

limiting the number of livestock. Some trade-offs can be managed through

measures to increase efficiency or through payment of incentives/compensation.

.....Other options may benefit food security or agricultural development

but not mitigation.”

......“There are still considerable knowledge gaps

relating to the suitability and use of these production systems and practices

across a wide variety of agro-ecological and socio-economic contexts and

scales. There is even less knowledge on the suitability of different systems

under varying future climate change scenarios and other biotic and abiotic

stresses”

Even without climate compliant objectives,

NGO agriculture programmes by and large are struggling to make an impact.

Otherwise we should not be having a global food crisis. Now climate

compliance becomes yet another addition to a long list of cross-cutting themes

- gender, disaster risk reduction (DRR), bio-diversity, caste, class, disabled,

linking relief, rehabilitation and development (LRRD) etc.

The more expansive the list of cross-cutting

themes, the more nightmarish field level staff should find to design and

implement a programme. In particular, project staff should be completely at

odds to resolve the dilemma how to achieve the needed levels of growth, but on

a lower emissions trajectory as it involves concerted effort to maximize

synergies and minimize trade-offs between contrary productivity and climate

compliance objectives.

If one billion of global citizens’ face prospects

of stark starvation, this is indeed a crisis of the gravest proportion.

Logically in such a situation we need to put all the available technological

options in our selection basket before selecting the best to solve the

problem. Instead we are offered a limited basket of choices - those remaining

after filtered through a climate compliance prism. For example Oxfam promotion

of exclusivity of choices is illustrated by their statement: ‘scope for increasing the area under irrigation is

disappearing; increasing fertilizer use offers ever diminishing returns.’ By limiting

choices, their seriousness to eliminate hunger and fight food inflation is open

to question.

NGOs have a tendency to implement

pre-determined solutions selected through ideological blinkers which is why

impact often eludes them. Many have not yet discovered Liebig's Law of the

Minimum which is a principle developed in agricultural science by Carl Sprengel

(1828) and later popularized by Justus von Liebig.

It states that growth is controlled not by

the total amount of resources available, but by the scarcest resource (limiting

factor). Accordingly, if seed material is a limitation for higher yield, it is

foolhardy to attempt quantum increase in yield by supplying more irrigation and

organic manure. We need to change the seed to get quantum jumps in yields.

Further to beat hunger and poverty, there are

three ways of increasing agricultural output:

1) Bringing new land into agricultural production;

2) Increasing the cropping intensity on existing agricultural

lands;

3) Increasing

yields on existing agricultural lands.

To beat a crisis as grave as Oxfam and

ActionAid paint it to be we need to leverage all these three options

simultaneously to obtain maximal outcomes. But here the Machiavellian agenda of

climate smart agriculture reveals itself as they either completely rule

out or put major road blocks to each of this options. The end result is that it

further contracts agriculture, accentuating food inflation, hunger and poverty.

OPTION

1: BRINGING NEW LAND INTO AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

One of the ways to increase food production

is by expanding the net area under cultivation. As an option, its leverage

potential to increase cropping yields is relatively more limited than the other

two options. The net sown area of the country has risen by about 20 per cent

since independence and has reached a point where it is not possible to make any

more appreciable increase. But its scope is higher if forests are encroached or

more expensively convert deserts and wastelands.

But the latter is ruled out as an option by

Oxfam because “it can release large

amounts of greenhouse gases”. But the same Oxfam on the other hand encourages

agro-forestry as ‘the income of an

average household involved in agro-forestry is around five times larger than

for any of their immediate alternatives (such as agriculture, small livestock

farming, or chestnut collection).’

Interesting. Oxfam’s whole report is all

about the planet fast hurling into a Malthusian trap and the need to ACT NOW to

eliminate hunger. But Oxfam's preference for agro-forestry over food crops

makes it clear that hunger is only a bogey for a larger, hidden agenda. Perhaps

Oxfam would have retained its credibility if they have been more forthright of

their preference for the planet over human beings and in that case their report

should have focused on saving forests and wilderness rather than human hunger.

Equally interestingly, the European Union

treats expansion of biofuel into forestry as meeting the criteria of climate

compliance while expansion of agriculture into forestry as a compliance

violation! As the prime mover of the climate smart agriculture model, the EU

policies reveal the eco-imperialistic character of this model.

Option

2: Increasing the cropping intensity on existing agricultural lands

Though both Oxfam and ActionAid in their

report do not overtly rule out this option of increasing cropping intensity, by

their obsession to climate proofing the agriculture viz, removing greenhouse

gases and thrust on organic agriculture, this by default could be assumed

as an impediment to climate smart agriculture practice.

[Cropping intensity refers to raising of a number of

crops from the same field during one agriculture year. It can be expressed as

Cropping intensity = (Gross cropped area / Net sown area) x 100]

Thus, higher cropping intensity means that a

higher portion of the net area is being cropped more than once during one

agricultural year. This also implies higher productivity per unit of arable

land during one agricultural year. For instance, suppose a farmer owns five

hectares of land, and gets the crop from these five acres during the kharif

season and, again, during the rabi season he raises a crop from three hectares.

He, thus, gets the effective produce from eight hectares, although he owns only

five hectares physically. Had he raised crop from only five hectares totally,

his cropping intensity would have been 100 per cent, while now it is 160 per

cent.

The index of intensity of cropping for the country as a whole is

reportedly to be around 160 per cent but shows great spatial variations. While

it maybe not sustainable to raise further cropping intensity in states like

Punjab and Haryana which have the highest copping intensity in the

country, states having less than the international average and arid and

semi-arid lands can be targeted to improve their copping intensity combined

with the thrust to make higher cropping intensity farming to be more

sustainable through options like irrigation expansion; crop rotation;

enhanced soil restoration practices etc.

Option 3: Increasing

yields on existing agricultural lands

Though many policies of Oxfam & ActionAid

are in the right directions, it is their climate compliant related components

of these policies that threaten to negate all these positives whose end results

bring about a contraction in agricultural production and/or add to food

inflation.

Irrigation and its Pricing

If the key input prices to agriculture go up,

it will add to the inflationary pressure on food prices. This should be a

no brainer. The converse also holds true. If prices of a key input of

agriculture decrease, it can help to ease inflationary pressure on food. So if

Oxfam is genuinely concerned about spiraling food inflation, it should support

policies that can deflate food prices. Instead, some of Oxfam’s policies

accentuate food inflation further e.g. calling to price irrigation higher.

As reflected in the USDA graph, net irrigated

area in India to gross cropped area has crossed more than 60% though accounting

for more than 90% of all agricultural production. Accordingly, if the price of

irrigation goes up, food prices go up in India.

Trade off between cattle and Organic Manure

According to Oxfam, cattle tops in terms of

their carbon footprint within agriculture. To reduce the cattle

footprint, logically their numbers must be reduced. And if cattle population is

culled, what happens to milk supplies and nutrition in the country?

That’s not the only chaos it creates. In

India, livestock provides significant contribution to agriculture through draft

power, fuel apart from manure. According to the World Bank, in the developing

world, milk and meat production alone can account upto 26% of the agricultural

GDP. Livestock is more important to the poor as a leveraging asset. In bad

times, animals can be sold. Selling livestock in hard times acts as a buffer

against loss of other assets, particularly as an insulation against land

alienation.

Oxfam and ActionAid reports do not divulge

what their positions regarding cattle are. So the moot question is whether they

want to reduce cattle population or increase it according to their plan to ‘building a new agriculture future’?

At the same time, Oxfam say that they want to

promote organic manures, a good proportion of which is accounted by farmyard

manure (FYM). So if they need to promote FYM on a wider scale, they would need

to increase cattle population by quantum leaps to ensure sufficient supply to

farmers all over the country. FYM though its nutrient content is relatively

lower, is the best option to improve the soil structure (aggregation),

enabling soil to hold more nutrients and water needed for the soil to improve

its fertility. Animal manure also encourages soil microbial activity, which

promotes the soil's trace mineral supply, improving plant nutrition.

But this is where Oxfam will find their

policy contradictions kicking in and find its elf in a dilemma as cattle top

their greenhouse gas emission chart and so expansion of its population is a

strict no-no by their climate compliant agriculture policy. If they promote FYM

without increase cattle population then this would spike FYM prices and keep it

out of reach of poorer farmers.

Consequently, it would be much simpler for

Oxfam not to promote FYM. But then, a large and key component of organic manure

would not be available to farmers, decreasing its effectivity as an operational

strategy. To compensate this loss, Oxfam would need to give a stronger thrust

to composts, entirely prepared out of crop residues. The problem is that such

compost though it could be high in nutrient value falls out short in its soil

restoration potential and hence take a toll of the ‘sustainability’ of their

model. Relative to FYM, the potential of composts to improve the soil structure

remains low. Among the different environmental characteristics, soil structure

is often neglected, although it has a strong impact on water and nutrient

access and uptake by the crop. If the state of the soil structure is unknown, a

crop malfunction can be totally misinterpreted and thus improperly corrected.

The other option for Oxfam would be green

manuring. But its use has several limitations. Water consumption by green

manure is a huge concern in areas less than 30 inches of rainfall that excludes

its use under semi-arid and arid conditions. Besides, nitrogen fixed in a green

manure crop is not a "free" source of additional N, but only

an effective option for a very small range of cropping systems, such as organic

crop production. There is also a cost to buy the seed, inoculate, and plant it,

and a cost to terminate the green manure crop at the right stage. There is also

the added opportunity cost of not growing a marketable crop in that year, and

greater depletion of soil moisture reserves in drier areas, compared to tillage

or chemical fallow options.

How the Oxfams and ActionAids under these

varying conflicting priorities evolve tradeoffs will be fun to watch. They are

damned if they do and damned if they don’t. But if they want to continue to be

accepted as one of the voices of developing countries, one trade off that would

do well to avoid would be attempting to reduce the cattle population.

Seed material as a strategic

choice for yield increase

Till the great drought of 1961, India used

traditional seeds, which despite several advantages possess the demerit of

being unresponsive to external inputs. Liberal inputs like water, fertiliser,

pesticides etc had little or no impact on yields, as it was limited by its

genetic makeup. So dump as much organic manure you want, the incremental

increase in yield would be nil or insignificant.

India then invited Norman Borlaug, the father

of Green Revolution to India, who introduced the high yield (hybrid) varieties

which were highly input responsive and this brought about a huge transformation

of Indian agriculture. From a net importer of food, India became a net

exporter. Productivity multiplied by a factor of nearly 10. The potential

of hybrids to enable yield increases is well illustrated by the story of

English Wheat. It took nearly 1,000 years for wheat yields to increase from 0.5

to 2 metric tons per hectare, but only 40 years to climb from 2 to 6 metric

tons per hectare.

The world population added about four billion

since the beginning of the Green Revolution and, without it; there would have

been greater famine and malnutrition. India saw annual wheat production rise

from 10 million tons in the 1960s shoot up to 73 million in 2006. The average

person in the developing world consumes roughly 25% more calories per day now

than before the Green Revolution. Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green

Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production

increased by over 250%.

Says Tuskegee University plant genetics

professor and AgBioWorld Foundation president CS Prakash:

The only thing organic farming sustains is “poverty and malnutrition.

Right now, roughly 800 million people suffer from hunger and malnutrition, and

about 16 million of those will die from it. If we were to switch to entirely

organic farming, the number of people suffering would jump by 1.3 billion,

assuming we use the same amount of land that we’re using now."

Economist Indur Goklany has calculated that,

if the world tried to feed just today’s six billion people using the primarily

organic technologies and yields of 1961 (pre-Green Revolution), it would have

to cultivate 82 percent of its total land area, instead of the current 38

percent. That would require ploughing the Amazon rainforest, irrigating the

Sahara Desert and draining Angola’s Okavango river basin!

So here lies the contradiction. If we were to

increase yields by 70% by 2050 as Oxfam aims to achieve and entirely depending

on organic farming as ActionAid expressed it would do, instead of facing a

triple crisis we would need at least to triple our present cultivated land.

But here kicks in the real problem. Oxfam in

the same breath say they want no further land expansion of agriculture as it increases

greenhouse emissions! If we were to do this and take to exclusive organic

food cultivation even as our population multiples, what do we get is mass

hunger and runaway food inflation on a scale which the world had not seen

before - the very issues Oxfam and ActionAid ironically ostensibly wants to

prevent.

Before the Green Revolution, almost the

entire agriculture was organic, using traditional seeds. The country’s

population in 1970 was then only around 555 million. So this can be treated as

a good baseline. It was because organic farming performed so miserably;

not being able to feed the population that India opted for the Green

Revolution. India was then a net importer of foods and virtually

dismissed as a basket case. The population in the country has since then

doubled itself in the last 40 years and agriculture growth rate is currently

double the population growth that explains why food supply is not a problem.

Amazingly we are now being told by the likes

of ActionAid that traditional seeds hold the key to future productivity rises!

Assuming they do, they do not tell us why they (traditional seeds) could not do

so before the Green Revolution and why there were unable to feed a population

which was only half its present size? Visit Mizoram, a NE state of India whose

agriculture even today is almost completely organic as it was before

Independence and what do we find? Agriculture is a dismal state and the state

is net importer of food. Since the population of the state has been growing, the

state’s food import bill has been growing in leaps and bounds since

Independence!

We have been also repeatedly told that food

accessibility for many people in the developing countries remains closely tied

to local food production (FAO 2008a,b; Bruinsma 2009). This maybe by and large

a truism but organic food lies outside its pale. You may ask why? This is

because organic food commands a premium both nationally and in export markets.

Because of this, poor farming families consider it more profitable to sell

their harvest rather than consume it. So the potential of organic food to

increase food security of the poor remains extremely low.

Oxfam calls for “breeding

drought-resistant and flood-tolerant crops”. Vandana Shiva, on the other hand argues there is no need

to breed new varieties as farmers have already bred corps that are resistant to

climate extremes. Though Vandana Shiva is absolutely correct she forgets

that being resistant to weather extremes is a very different trait from also

enabling high yields. This is the benefit of hybrids as they can combine many

traits. So in this case, Oxfam maybe on the right track except that they are

increasingly suspected as acting as the Trojan Horse of the Monsanto-Bill Gates

Foundation Axis for Genetically Modified (GM) seeds.

GM seeds, as we know, now command more than

95% share of the cotton seed market in India, despite NGOs and environmentalist

huge opposition to it. The story of cotton enables us to use as a classical

case study to understanding the mind of the farmers. The very fact farmers en

masse discarded traditional cotton seeds for GM seeds reveal their overwhelming

desire for quantum jumps in yield increases.

But GM seeds are nothing but hybrids encoded

with a GM gene, where yield potential is determined by the hybrid while all

what the GM gene does is enabling protection against one or a small range of

pests, and thereby reducing yield losses from pest attacks. The main drawback

of GM seeds is that it is creates pest resistance during the medium-long term.

Its impracticality is highlighted by the imperative to keep 20% of the area

under cultivation as refugia, which shrinks available cultivable area, a luxury

for a country like India.

To prevent resistance build up in, pesticide

management should reflect its judicious use - finding the right toxin-pest fit;

right dosage-degree of infestation fit combined with timely and required

frequency of applications. The endotoxins secreted from Bt violate all these

conditions and curiously neither Action Aid or Oxfam do not firmly take a

position on GM seeds. So while GM maybe a possibility in the future, it still a

very work-in-progress technology. Read our archives: As Bt Cotton

turns 10, observational data certifies it a Super-Flop

So continuing productivity increases, as of

now, need to rely on high yielding varieties (HYV) or hybrid seeds. Yields

may have plateaued which is different from saying there are declining. This

plateau is still at least higher by a factor of at least 5 as compared to the

time of Independence when agriculture was entirely organic. Within this

context, unless a technological breakthrough appears, there is no alternative

but to continue dependence for hybrids.

No comments:

Post a Comment