Just when it looked as if a traditional El Niño was getting its sea legs, the event is now looking a bit less canonical. This prompted the following analysis. This post is jointly written by Rajan Alexander who administers the blog, Rajan’s Take: Climate Change and Rajesh Kapadia who administers the blog, Vagaries of the Weather.

The Indian press has been going gaga, spreading hysteria about the supposedly El Niño effect messing up the current monsoon. After June whetted their appetites of gloom with very poor rains, their prophecy of doom has now hit a huge speed break with the apparent monsoon revival seen so far this month.Bob Tisdale is perhaps one of the world’s best known authorities on sea-surface temperatures and related oceanic climate phenomena. In his blog he observed that an analysis of historical data suggests that the (summer) El Niño usually crossed its threshold values by late May. This year, it did so only by June second week. Since theoretically there is a time lag of at least 3 months for any El Niño effect to significantly impact the monsoon, this delay could give the current monsoon season a reprieve of sort.Going by the current rate of El-Nino development, the earliest it can impact the monsoon is most likely by beginning of September, a month which accounts for less than 16% of total rainfall of the South West Monsoon (SWM). This also raises hope that August rainfall may have a fair chance of recording “near” normal rainfall viz. around 93-95% of Long Period Average (LPA).Comparison of the evolutions of El Niño eventsBob Tisdale’s latest post compared the current El Niño’s evolution with others historically. The following are his findings:1. NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies (a commonly used ENSO index) have been above the +0.5 deg C threshold of an El Niño for 4 weeks. While it’s far from an “official” El Niño, it appears that it’s likely to become one.

The first thing that stands out in the graph is how there really is nothing typical about the evolution of El Niño events. Five started from ENSO-neutral conditions; that is, with NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies between -0.5 and +0.5 deg C.

Five, including the current one, started from La Niña conditions, with the NINO3.4 sea surface temperatures cooler than -0.5 deg C. And there’s the outlier, the 1987/88 portion of the 2-year 1986/87/88 El Niño.Other than having the coolest NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies at one point, there’s nothing remarkable about the evolution of the NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies this year.

2. The graph below compares the evolution of the El Niño events that started from La Niña conditions. This year’s NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies had been tracking along at the pace of the most recent El Niño, the one that occurred in 2009/10, until recently. Over the past two weeks, NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies have been cooling.

3. NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies appear as though they’re being suppressed by the cooler-than-normal waters being circulated southward from the North Pacific, which should be feedback from the back-to-back La Niña events.It will be interesting to see how long the cooler waters from the North Pacific can suppress the central sea surface temperatures in the east-central equatorial Pacific.

4. The NINO1+2 region is in the eastern tropical Pacific, just south of the equator. The coordinates are 10S-0, 90W-80W. This year the NINO1+2 sea surface temperature anomalies warmed before the NINO3.4 region, but they also have been cooling.

5. There’s still a pocket of elevated anomalies at depth in the eastern equatorial Pacific, and there’s a long way to go before the peak of the ENSO season.

El Niño Modokai

Till recently, it was thought that the El Niño had only one mode - a periodic warming in the eastern tropical Pacific that occurs along the coast of South America. In 2004, it was discovered to have also a second mode that occurs around 12% of the time.A Japanese team led by T. Yamagata (that included a prominent Indian climatologist, Dr Venkata Ratnam) noticed the 2004 El Niño was warming more strongly in the Central Pacific region and accordingly stumbled on the discovery of its second mode by sheer accident. They called such an El Nino as Modokai, which is a classical Japanese word which means “similar but different”. The phenomenon is also known as a Pseudo or Central Pacific (CP) El Niño. It was then adopted by K Ashok and colleagues in a 2007 Journal of Geophysical Research paper to refer to central-Pacific–weighted El Niños more generally. Its basic signature is as follows:1. Weakening of equatorial easterlies related to weakened zonal sea2. Surface temperature gradient lead to more flattening of the thermocline.The US, CPC-International Research Institute in a press note said average sea sub-surface temperatures persisted in the far eastern Pacific and had recently spread westwards. This has taken place in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific but recent values of upper ocean heat anomalies continue to reflect ENSO neutral conditions. Equatorial sea surface temperatures (SST) are greater than 0.5°C above average across the eastern Pacific Ocean though the atmospheric circulation over the tropical Pacific reflects cool-to-neutral ENSO conditions.So there we have sort of a confirmation that the Niño is moving westwards instead of the typical eastward direction.

Further - just when it looked as if a traditional El Niño was getting its sea legs, the event is now looking a bit less canonical. Just take a look at last week’s US-CFS v2 forecasts for Niño regions 1+2 from where it could be observed that the warmest anomalies have been centred in the eastern portion of the ENSO monitoring area.

However, as also seen in the forecast, there is now more of a potential for the temperatures to be much lower. One explanation is that the Niño maybe dying off!! The only other explanation is that the heat is merely transferring westwards - a fact validated through the latest SST departures. The western bias to this summer’s warming pattern is what brings to suspect an El Niño Modoki development rather than a typical El Niño.

The question is that if the heat transfer is taking place westward instead of eastward as typically, are we seeing an El Niño Modoki developing instead of a normal El Niño as commonly assumed? This is not easy to answer as Niño regions 1+2 also appears now to be cooling off along with NINO3.4 SSTs. However such cooling could be temporary and not unusual.So what’s an El Niño Modokai?But before we can understand El Niño Modokai variant we need to have to understand El Niño itself. It is part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) that alternately gives us warm El Niños and cool La Niñas.An ENSO is a physical oscillation of ocean waters from side to side of the tropical Pacific Ocean. It is kept going by trade winds that push the water westwards along the north and south equatorial currents. Between these two currents is the equatorial counter current and the water piled up in the western Pacific eventually comes back east via that counter current. It does so periodically as a massive wave, observable as a Kelvin wave, because the oscillation is caused by wave resonance and the resonance period is determined by the dimensions of the ocean basin.As and when an El Niño wave reaches South America at the equator it splashes ashore and spreads out. This creates a large area of warm water, the air above gets warm, an updraft forms that interferes with trade winds, and global temperature rises by half a degree Celsius. But any wave that runs ashore must also pull back. As the El Niño wave retreats water level behind it drops half a meter or more, cold water from below wells up to fill the space, and a La Niña gets started.But in the case of Modokai, only 20% of the time a La Niña emerges. More often, the Niño dips below the La Niña threshold, but do not remain there long enough to be considered an official La Niña. So if an El Niño Modokai is indeed confirmed this year, it is most likely next year we should be having an ENSO neutral year, rather than a La Niña year. This means, if the El Niño factor is considered as the prime one, we can expect 2013 monsoon season to be within the normal-above average range.Modokai is but a chaotic variation of a typical El Niño pattern, absent the current gyres that usually form at the eastern terminus. This unique warming in the central equatorial Pacific associated with a horse-shoe pattern is flanked by a colder sea surface temperature anomaly (SSTA) on both sides along the equator. This year, as seen in the above graph, there is a lot of cold water circulating from Alaska down the west coast of Canada, the US and Mexico. This cold water is mixing with equatorial Pacific waters and keeping SSTs in equatorial Pacific down.The real difference between the normal El Niño and El Niño Modokai isn’t their locale within the Pacific, it is the mode of energy release and it’s spreading out. The former is predominantly a localised event at the sea surface, because a huge spike in humidity which traps emerging energy and spreads it globally via the resulting winds.Whereas El Niño Modokai is more a global emission of energy from the ocean, resulting in a general humidity increase worldwide rather than a localised blanket of water vapour around a localised emission event, followed by rapid heat loss to space once the warm air is spread out. That is why lower tropospheric temperatures can be expected to remain high as long as 4-6 months after the Pacific event petered out.So from this month to maybe first quarter next year, global temperatures maybe expected to spike moderately and maybe the last hurrah for global warmists. Once the event is over, global lower tropospheric temperatures can be expected to fall very fast, particularly once the NH winter kicks in. Due to the loss of humidity over the cold land masses; the 2014 northern hemisphere winter could be expected to be extremely cold.El Nino Modokai’s Effect on WeatherIn a paper by Venkata Ratnam et al entitled “Pacific Ocean Origin for the 2009 Indian Summer Monsoon Failure”; effect the following were postulated as effects of El Niño Modokai on weather:

During the boreal (northern hemisphere) summer season rainfall anomalies during the June-September season of the seven positive El Niño Modoki years 1986, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1994, 2002, and 2004. Statistically significant surplus rainfall anomalies are seen in the central equatorial Pacific region flanked on both sides by the negative rainfall anomalies in the equatorial western and eastern Pacific.The atmospheric condition associated with the western pole located in the equatorial western Pacific is strongly suspected of influencing rainfall from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore etc, with the teleconnection extending northwest up to south India and also Sri Lanka.The teleconnection associated with the positive rainfall anomaly in the central pole (equatorial central Pacific) seems to extend westward via the Philippines, Myanmar to northern eastern India.In the East Asian region, southern Japan suffers droughts during these years owing to the Pacific-Japan pattern [cf. Nitta, 1987]. The deficit rainfall in the western Pacific region is seen to extend southward to southeastern Australia, influencing a significant part of eastern Australia. The negative rainfall anomalies over the equatorial eastern Pacific extend over western coast of North America.The result in the Pacific Ocean is less wind shear and therefore more hurricanes/cyclones - the warmer water is also a necessary factor. The result in the Atlantic Ocean is more wind shear and fewer hurricanes/cyclones.El Niño Modokai Index (EMI)

The Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science & Technology (Jamstec) developed an El Niño Modokai Index (EMI) as above. The index currently shows that the EMI is still weakly negative but expected to turn weakly positive by this month end or during August.

An El Nino Modoki event is called ‘typical’ when its amplitude of the index is equal to or greater than 0.7α, where α is the seasonal standard deviation. This means even if what is developing is indeed an El Nino Modoki though presently mistakenly assumed an El Niño , this could be confirmed at the earliest only by end of September or October though we could possibly have the first preliminary indication by August end.Past Impact of El Niño Modokai (summer) on Indian Monsoon

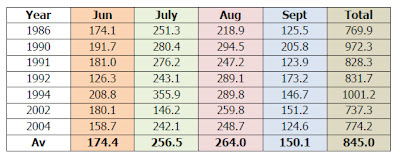

Seasonal rainfall wise, there seem to be alot of variation within El Niño Modokai years ranging 769.9 (87%) to 1,001 mm (113%) of rainfall of Long Period Average (LPA). The average however is 845 mm or 95% of LPA.

Instead of around 175 mm average rainfall for June, this year the country received 115.5 mm or a 29% deficiency. If this year is indeed an El Niño Modokai year, then this should be a new record low relegating 1986 to second place.With June rainfall poor, does it mean rainfall would get progressively worse? Let’s look at 1992, presently occupying the bottom rung with a 27% rainfall deficiency in June. At the end of the season it still managed to reduce the deficiency to 6% overall. So it is possible that July-September rains to be normal even if June rains fail.However, this is a simplistic analysis. The performance of the monsoon will depend on other variables such the behaviour of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD); Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), summer temperatures, snow cover, Mascaerne Highs, etc. Nevertheless let’s use the same technique to understand what possible impact El Niño Modoki could have in relation spatial distribution of rainfall as demonstrated historically.

We find that North India, both east and west, relatively tend to suffer a higher rainfall deficiency as compared to the Southern Peninsular with Central India coming out practically unscathed.ConclusionWhat we can conclude with high confidence is that with the El Niño crossing threshold values two weeks later than normal, this is likely to be a positive development in relation to rainfall for rest of the monsoon season.Should the El Niño be of the Modokai variant, then its adverse impact on rainfall is most likely to be relatively weaker than those of a normal El Niño.It is too early to confirm the development of an El Niño Modikai this season. We should have better idea by mid August but an official confirmation would be possible only after the monsoon season ends.

Excellent post. Even though I didn't understand all of it :)

ReplyDeleteThanks,

Hi Rajan,

ReplyDeleteCould you recommend any books on basic meteorology and the monsoon? I am currently reading Air Apparent by Mark Monmonier which is very good.

BTW you may want to read this paper http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2012/20120105_PerceptionsAndDice.pdf . This conclusions drawn about AGW are different from yours. Still...

Thanks tons,

I came across this one - http://theweatherprediction.com/basic/guide/

DeleteI am sure they are more than one view on Climate Change. What's more important is not what others perception but your own.