Media has apparently gone totally berserk declaring the monsoon dead even as it just arrived. Their headlines scream that June rainfall was deficient by a whopping 29% and that 83 per cent of the country, including India’s granary states of Punjab and Haryana, receiving deficient or scanty rainfall so far.Self-titled “Food Security Analyst”, Devinder Sharma of the NGO sector and one of founder members of Indian Against Corruption, also joined the scare mongering tamasha when he warned during an interview to a news channel, of the prospect of a negative agricultural growth rate due to a likely El Niño effect. This, Sharma added, will further accentuate the downward pressure that the overall economy is currently experiencing, that has seen our economic growth rate slip below the 7% levels - the first time over almost a decade!It was left for Deputy Chairman of India’s Planning Commission, Montek Singh Aluwalia to strike a word caution to journalists:"It’s not the date of the onset of the monsoon; it's the overall level and distribution over the next four months. You can have a situation where the monsoon is absolutely on time and then it peters out. You can have a situation where the monsoon is one week late or even 10 days late built then is healthy."

CLICK TO ENLARGE

As seen from the above table, June accounts on an average only 18% of the total rainfall during the South West Monsoon. The monsoon had been demonstrating a pattern change in recent times where the rainfall in June had been decreasing while those in July increasing. Such a change in rainfall pattern is often used as one of the “evidences” by NGOs and environmental groups for the building their case of “catastrophic climate change”.In reality; such a change may even be beneficial for agriculture. Though such a trend may result in delayed sowing, the excess rains in July tends to leave sufficient soil moisture for standing crops to tide over in the eventuality of August rainfall failing to live up to expectations. This makes the performance of July rains absolutely the key month to agriculture growth rate. It is failure of July rains that could prove “catastrophic” for Indian agriculture.Rains can accordingly fail in June but if July records near normal or even above average rainfall, we can be fairly optimistic that this year’s agricultural growth will end up in the green. While a 29% rainfall deficiency for June (124 mm of rainfall as compared to 163.6 mm average) may per se look rather depressing, it has to be kept in mind this only 40% of the deficiency that the country suffered for the same month during the 2009 monsoon season - also another El Niño year.In 2009, the June rains were a whopping 47.2% below a 50-year average called as the long period average (LPA). The 2009 El Niño was one of the strongest in recorded history and despite this, the country managed +0.4% agriculture growth rate, suggesting that through irrigation expansion over the years, the vulnerability risk of our agriculture to poor monsoons have significantly reduced. Punjab and Haryana, the granary of the country, for instance have 93 per cent of their arable land irrigated and such heavily insulated against a monsoon failure. There is no reason why this year should be any different. In fact, we are better place this year than ever to register a new bumper food record. Whatever momentum in growth rate in agriculture lost during the Kharif season could be offset in part or whole by the expected bumper rabi crop this year. While El Niños negatively affect the SW Monsoon (SWM), it has an extremely favourable influence on the NE Monsoon.

On an average, the country receives around 887 mm of rainfall during the monsoon months - June-September. A 29% deficiency for June still adds up to just a 4.93% deficiency in the 887 mm total average SWM rainfall. Such a shortfall could be possibly made up either in part or whole during the next three months of the monsoon performance. This is really the crux Montek Singh Aluwalia tried telling journalists.As far as agriculture is concerned, it is not even necessary for the monsoon to perform 100% of its Long Period Average (LPA). What matters are what its performance is during the month of July-August and its spatial distribution during these two key monsoon months. While a 10% deficiency of rainfall from its mean by itself should not pose a problem to agriculture, what is more critical is its spatial distribution.

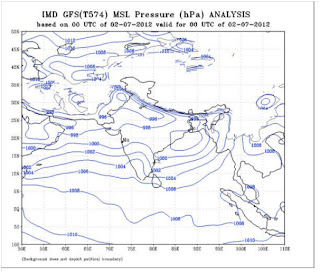

This is particularly true this year as what concerned meteorologists more is not so much the mean rainfall for the country but the alignment of the monsoon troughs. It was the alignment of the north-west monsoon trough that initially (in June) posed a problem while the north-eastern bay trough was found well developed. Such a formation however was not helpful for rest of India since entire moisture gets offloaded in the area of the trough here that explains the Assam floods. But the situation now has changed.A study published in the International Journal of Climatology in 2009, carried out by Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) Director BN Goswami et al showed that the monsoon is demonstrating a new pattern taking more time to reach the northern parts of the country. Instead of the normal onset date of June 15, the onset at Nagpur is now taking place on June 18 with the Arabian sea branch more active than the Bay of Bengal branch - the slowing of monsoon being linked to the weakening of the wind shear. Wind shear is the difference in the wind speed at 1.5 km and at 12 km above the land surface.While most global models have indicated a deficient monsoon (below 90% of LPA); the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD)’s forecast is 96% of LPA viz. a “normal” monsoon. Since the model error of IMD is + 5%, their forecast in reality is between 91-101% of LPA, which means, despite the 29% deficiency in June rainfall, the IMD is still very much on target. So is this blog - our revised forecast last week was 94% of LPA or between 91-98% of LPA at 95% confidence level! We see no reason to revise this forecast further downwards. So don’t rule us or the IMD out just yet. If rains fail in July, then please by all means announce the demise of this season’s monsoon.

El Niño: How much of this scare is real?

The media and NGO scare paints the El Niño factor as the main monsoon spoiler. According to the latest available data, we have now decisively crossed El Niño threshold values at the end of last week with Niño 3.4 at + 0.6ºC and Southern Oscillation Index (SoI) at -10.4. These threshold values need to be maintained for the next 3 months before an El Niño episode can be officially confirmed.

However global models as seen above remain split whether an El Niño will develop for the monsoon period July-Sept but more unanimous in projecting an El Niño from September. The Tokyo-based Regional Institute for Global Change (RIGC) in May told Hindu-Businessline that the warm sea surface temperature anomaly near the eastern boundary of the Pacific may disappear towards the end of the monsoon. The ‘neutral’ state (neither El Niño nor La Niña) will return to the east Pacific basin, and may continue until March-April next.

The POAMA model’s ensemble mean projecting weak El Niño conditions during the remaining monsoon months - July-September - could be observed below:

CLICK TO ENLARGE

One factor many forecasts overlook is that there is always a time lag between an El Niño and its impact on the monsoon which could be anywhere between 3 -6 months. This practically means September is the earliest, if any, it can impact the current monsoon, as the IMD correctly assumes. So for all practical forecast purposes, even as critical indices cross El Niño thresholds values and intensifies further, as far as its impact on the monsoon, it is fairly negligible. It’s almost as if ENSO neutral conditions exist right through June to September for forecasting purposes.But even assuming weak El Niño effects prevails during July-September, is this sufficient condition for the media and NGOs to declare the monsoon dead on arrival?So let’s look at the IMD data according to which there have been 36 El Niño years since 1875 and the table below shows how they panned out in terms of rainfall:

So for El Niño years, there is a 44% probability for rainfall less than 90% of LPA; 39% probability for rainfall falling between 90-100%; and only 17% probability for above average rainfall. There are two ways to look at this data:

a. The probability of rainfall below 90% of LPA is the highest at 44%, so it is assumed the most likely outcomeb. The probability of rainfall above 90% of LPA is the highest at 56%, so it is assumed the most likely outcome.

The monsoon forecasts of most global models and my friends in the independent weather community - Rajesh Kapadia of blog Vagaries of Weather and young Akshay Deoras of blog of Metd Weather converge on predicting deficient rainfall, probably conditioned by outlook (a) while I find myself clubbed with the IMD forecasting a “normal” monsoon under outlook (b).While there is no significant difference between global models and IMD’s track record in monsoon forecasting, both Rajesh and Akshay are seasoned forecasters with a huge fan following as compared to me, who is a practical rookie in the field. So it appears my forecast of “normal” monsoon is swimming against the tide and the thought that I have the IMD as the only company is obviously very much discomforting. Nevertheless, I see no reason why the need to downgrade my forecasts of a normal monsoon, at least at this stage of the monsoon.There also seems no 1:1 correlation between the strength of the El Niño and rainfall. In 1997 the country received excess rainfall amidst the strongest El Niño in the last century. The effects of the El Niño apparently then was swamped by an equally strongly positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). The interplay between El Niño and the IOD therefore can often explain the major difference in outlook among monsoon forecasts. Global models like those of the Regional Institute of Global Change (RIGC), Tokyo and Akshay’s anticipate a strong likelihood of a negative IOD concurrent with a weak El Niño conditions that leads them to forecast a deficient monsoon whereas this blog assumes a weak El Niño concurrent with a strong likelihood of positive IOD conditions that should explain my forecast of a “normal”monsoon.

Review of other Climatic Factorsa. Positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)

CLICK TO ENLARGE

As the POAMA dynamic model projects, the IOD is expected to shift fairly strongly positive mode this month that augurs well for monsoon rains. This by itself may not guarantee normal rainfall but what it can be certainly expected to do is to mitigate the El Niño effect to some degree or other, particularly so as the El Niño is expected to be only of a weak to moderate strength this year. We have the 1997 monsoon as a good example of the IOD’s ability to even totally swamp the effects of one of the strongest El Niños in recorded history.

But DS Pai, Director, Long-range Forecasting, IMD admitted to Economic Times:“There are two phases of IOD - negative and positive. While the positive phase assists rains, the negative phase doesn't. There is a threat that IOD, which is currently slight positive, may turn to negative or neutral".Translated: We expect a positive IOD but there is a threat we could instead get a negative or neutral IOD.So what happens during a negative IOD?In the negative phase, as in the instant case, the sea surface warms up to the east of the ocean basin relative to the west. This causes convection and precipitation to be confined to the East Indian Ocean, robbing mainland India of its share and affecting rainfall.This is exactly what happened in June where the IOD was mildly negative. Now if the POAMA model is to be believed the IOD is shifting to its weak to moderate positive mode, which should ensure more even spatial distribution of rainfall within the country.

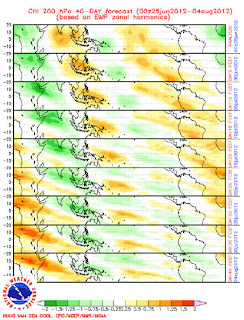

b. Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO)

The MJO that was one of major factors responsible for poor rainfall experienced during the month of June. But as seen in the above CPC-NCEP-US forecast, the MJO is shifting mode from this week and expected to stay that way till July end, if lucky, maybe till mid-August. We should accordingly expect good rains all through July. If it is further assumed that rainfall in August is near normal (around 95-7% LPA) and September could mimic the scanty rainfall experienced in June, we should end up overall with a mean around 94-96% of LPA supporting a fairly decent agricultural production season.c. Monsoon Trough AlignmentThis year looks an exception with the south-east monsoon trough well developed unlike past years and this explains the excess rainfall in the East and North-East of the country. A typical monsoon-season low pressure system or depression over the northern Bay of Bengal is needed deliver good rainfall over the subcontinent. The sea surface temperatures (SST) in the northern Bay of Bengal need to become favourable for such systems to emerge viz. it needs to be slightly warmer than average and higher than the SST in the equatorial Indian Ocean region.

In June, the north-western bay was relatively lower in temperature than the SST in the equatorial Indian Ocean region. This was because of a negative IOD, the sea surface warms up to the east of the ocean basin relative to the west. This causes convection and precipitation to be confined to the East Indian Ocean, robbing mainland India of its share and affecting rainfall. Since then the IOD has switched to mildly positive and if the Australian POAMA model is to be believed than it gets moderately stronger this month that augurs well for more even spatial distribution of the monsoon in the country.

The long-persisting monsoon trough linking the North and South of north-east India has been blamed for extremely heavy rainfall in Assam. The south-east alignment across the plains has to change to a north-west alignment if north-west India that includes the country’s granaries (Punjab & Haryana) has to see some rainfall of some significance.

A full-fledged, low-pressure is one possibility of enforcing this change in its bearing. This shift in alignment could be triggered by the system now developing in the Bay of Bengal as global weather model forecasts are now indicating that the Bay could undergo a significant churn during this week. This Northern Bay low is likely to move into the north-western regions from today.

As mentioned earlier, active monsoon conditions require a weather system in the Bay to which the eastern end of the monsoon would be anchored allowing monsoon easterlies to fill the trough and pour their contents over adjoining land and if strong enough, even penetrate into peninsular India with a rain-head, breaking through the “Northern Limit” and bring rains to the north western parts of the country. This flow is a continuation of the south-east trades, altered to south-westerlies by the Coriolis force as they move north, across the equator, bringing huge quantities of water vapour, and reaching the west coast of India as the south-west monsoon.

The Arabian Sea branch is stable since June 17, the Bay of Bengal branch is static since June 21. In fact, after entering UP on June 21, the wind pattern changed from easterly to westerly, which diverted the monsoon towards northeast leading to widespread rains in Assam, resulting in floods. Now, the easterly winds have gathered momentum again due to formation of cyclonic circulation over the Bay of Bengal. These winds are expected to make monsoon currents over the northeast recurve towards UP and upwards. The Northern Bay low should expectedly bring relief to the water parched north-western regions of the country later this week. How long this relief will last is hard to speculate?

Meanwhile, the Arabian Sea arm is being aided by a NW Bay Upper Atmosphere Cyclonic (UAC) circulation which is expected to move inland and hit New Delhi by Friday. The IMD in a press note last evening forecasted:"Conditions are favourable for further advance of southwest monsoon into remaining parts of Maharashtra and some more parts of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh during next 48 hours."More re-assuring is that maximum temperature heat wave to severe heat wave conditions are prevailing over some parts of Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and north Madhya Pradesh. The highest maximum temperature of 46.0°C has been recorded at Churu (Rajasthan) yesterday. The situation was no different in other parts of northern India, Lucknow, Allahbad, Jaipur, Agra all registered temperatures in forties.

These heat wave conditions prevailing now in the north western regions could trigger the needed shift in the north-west alignment of the monsoon trough. The hot air over the land tends to rise, creating an area of low pressure. This creates a steady wind blowing toward the land, bringing the moist near-surface air over the oceans with it. Also aiding the process is a positive IOD during which winds over the Indian Ocean blow from east to west are likely to increase from this month.

A seasonal low now exists at 996-8 mb, and the ridge around Kerala at 1002-4 mb, building up a fairly good gradient to pull the monsoon inland. An equally strong pressure differential exists on the north-eastern bay side. Faster advance of the monsoon can be expected from this week as cyclonic circulations will be in action from both sides - Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. The Northern Limit of the Monsoon should be decisively breached with the monsoon covering the entire country by this weekend or certainly by next week. No wonder the IMD is sounding exuding confidence:

“Analysis of current meteorological conditions indicates increase in rainfall activity over east, central and also over northwest India due to development of seasonal east-west trough with embedded upper air cyclonic circulation,”d. Cloudiness

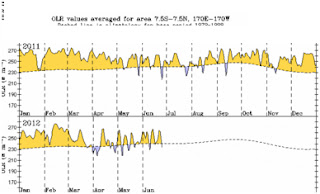

While Niño 3.4 and SoI critical indices have exceeded El Niño threshold values, the atmospheric is still partly La Niña like as seen in observed values for cloudiness. There can be no rains without clouds and as admitted by the IMD, this was one of the favourable factors that prompted them to predict a normal monsoon.

Rajan,

ReplyDeleteThis is an excellent post and an excellent blog.

I am very interested in the science of the monsoon and have been searching on the web for a blog of this sort.

Thank you,

Regards,

Hi Vivek. Thnx If the IMD despite over 100 years find it difficult to forecast a monsoon, its a learning curve for everyone. I'm just an amateur

DeleteRajan, Very good and practical analysis. A thorough and detailed explanation combines all my blogs, its an all in one with a better presentation and graphics.

ReplyDeleteBTW, Rajan, please be corrected for one point. I have never stated of an over all deficient Monsoon for this year. When the El-Nino factors were expressed, I have mentioned in my (MW-8)that for now "lets not worry about the El-Nino at this stage."

I go cautiously month by month, and have put up the estimate for JULY ONLY.

IN fact, all my previous MWs also , I was careful not to be lead away with a full season forecast.

Thanks and regards,

Rajesh.

Thnx Rajesh. I actually picked the fundas from your forecasts. If not for that I won't dreamt of writing this piece. Sorry about the error. Since climate is a choatic, non-linear system, that's the way to proceed - dynamic analysis - as variables change, analysis change. Thnx again

ReplyDelete